Sometimes ghosting is for people who value their own peace of mind, who predict that saying “sorry, I don’t want to be contacted further” will either cause drama or be ignored.

Lvxferre

The catarrhine who invented a perpetual motion machine, by dreaming at night and devouring its own dreams through the day.

- 18 Posts

- 2.02K Comments

Plenty people. For stuff like

- insisting on a subject after I clearly said “I don’t want to talk about this”

- throwing a tantrum against me for something that is clearly not my fault

- sending me multiple messages sequentially, containing nothing of value

- trying to proselytise their stupid superstition, whichever it may be

- bossing me around with uncalled advice, after I said to drop it

And I don’t feel bad for ghosting any of those. At all.

7·9 hours ago

7·9 hours agoMy two choices:

- Pontic Steppe, around 3000 BCE. Likely region where Late Proto-Indo-European was spoken.

- northern Lazio, around 650 BCE. If possible/reasonable I want to spend a bit of time in an Etruscan city, then in a Faliscan city, then in a Sabine one. I’m OK travelling by foot if necessary, as long as there’s always people talking around me.

In both cases I want to be able to record everything people say. Preferably video, but audio is good enough. I just want to know better about languages of the past.

It’s kind of tempting to include 1450 Uruguay as a choice, since we barely know anything about the Charrúa language. However the Charrúa weren’t exactly friendly to outsiders, so this option would be only if neither side can interact with each other.

1·10 hours ago

1·10 hours agoOriginally Anglish was a lot like Siegfridisch - a single guy (Paul Jennings), replacing borrowings with new expressions coined from native words, just for fun. Jennings framed this as how English would be if the Normans were defeated in 1066, and he published it in a satirical magazine (Punch).

It does look more serious nowadays, though. Anglish started out in 1966, and the people picking the idea up focused a lot on making it more consistent. (And also because Jennings wasn’t being as playful as Zé do Rock.)

Kind of off-topic, but can you believe that practically nobody knows Zé do Rock here in Brazil? Even if a chunk of his stuff is written also in Portuguese. (He also plays with the language, his “brazileis” is… weird, but in a good way, to say the least.)

2·14 hours ago

2·14 hours agoI get what you say, and I agree; but when it comes to the average user I wonder if they’ll even get it. They don’t think on the grounds of a “protocol” or a “platform”, it used to be “site” and now “app”. They do it even with email, of all things, even if it’s one of the oldest cross-platform protocols out there!

1·15 hours ago

1·15 hours agoThey tolerate each other enough to get each into a corner and not interact much.

And yet that is not what we see in the Fediverse. Those “corners” don’t exist here.

6·15 hours ago

6·15 hours agoThat is correct but it does not contradict anything that I said.

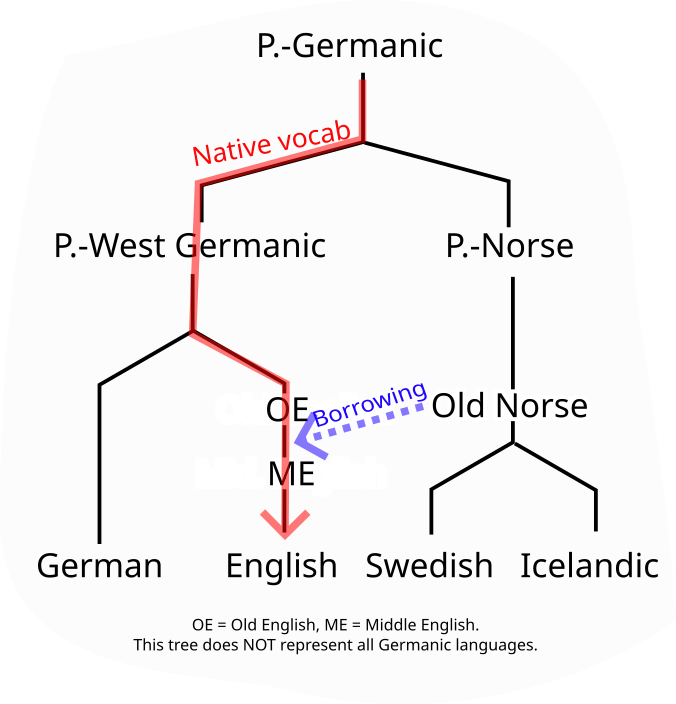

Even if Old Norse is Germanic, Old Norse words in English are still borrowings. “Borrowed” does not mean “not Germanic”, it means “not inherited”, both things don’t necessarily match.

This is easier to explain with a simple tree:

Only words going through that red line are “inherited”. The rest is all borrowing, the image shows it for Old Norse words but it also applies to French (even if French is related to English - both are Indo-European) or Japanese (unrelated) or Basque (also unrelated) etc. words.

But I digress. In Anglish borrowings from other Germanic languages should still get the chop, as seen here and here.

From a quick glance The Anglish Times does a good job not using those borrowings. The major exception would be “they”, but it’s rather complicated since the native “hīe” became obsolete, and if you follow the sound changes from Old English to modern English it would’ve become “she”, identical to the feminine singular. (Perhaps capitalise it German style? The conjugation would still be different.)

9·17 hours ago

9·17 hours agoThe people here and their attitude towards people who don’t agree with them are the problem.

And that’s a structural problem. The ActivityPub was supposed to allow both the “average person” and the “nerd” to coexist in the same platform, without one getting too much in the way of the other; it doesn’t.

I’m not sure on a good solution for that.

22·18 hours ago

22·18 hours agoIt’s all fun and games until venture capital kicks in, and exploits that central user data store to further centralise the rest of the network. Even then yes, I think that Mastodon has a lot to learn with Bluesky, on how to make user experience smoother.

7·20 hours ago

7·20 hours agoso Germanic words are fine

Not all Germanic words; it depends on how they found their way into the vocabulary. For example something like “sky” should be still removed, even if Germanic - because it’s an Old Norse borrowing.

21·20 hours ago

21·20 hours agoThat’s an interesting experiment. I like how it “vibes” from informal to ancient.

42·15 hours ago

42·15 hours ago“Friendly” and “land” are inherited, not borrowed. Those are two different processes and Anglish only gets rid of the words from one, not from the other.

“English” is not a mix; “English vocabulary” is. (Just like the vocab of most other languages.) A language is not just its vocab just like a mammal is not just its fur. The core of the language (its grammar) is pretty much what you expect from a Germanic language after some aggressive erosion of the case system.

English didn’t get many words from “German”; the inherited vocab is from “Proto-Germanic”. The name might be similar but they’re different languages, Proto-Germanic is the parent of English, German, Swedish, Icelandic, Gothic, etc.

People often point out the “French” (actually a mix of French and Norman) loanwords in English. Sure, there’s a lot of them, but as Anglish shows they aren’t structurally that important. On the other hand, the text couldn’t get rid of “they”, even if it’s a borrowing from Old Norse - the old third person plural “hīe” would probably have ended as “she”, just like the feminine singular.

EDIT: if the downvotes are due to some incorrect piece of info, please, say it. I tried to make the comment as accurate as possible, but something might’ve slipped, dunno.

Alternatively, if something that I said is unclear, please also say it and I’ll do my best to clarify it.

I left Debian but Debian didn’t leave me, it seems…

2·2 days ago

2·2 days agoNot to my knowledge. However, there are plenty references to bees in the whole mythology.

For example, the priestesses of Demeter (Olympian goddess of the soil, crops and food) were typically called μελισσαι melissai “honeybees”; and Persephone (goddess of the spring and underworld; Demeter’s daughter) got quite a few honey-related epithets, such as Μελινδια Melindia and Μελινοια Melinoia (both with μελι meli “honey”).

171·3 days ago

171·3 days agoBrazil is a Bad Idea®.

- There’s a reasonable chance that a Trump-like clown wins in 2026. Probably a Bolsonaro ally, or even a relative (there have been talks about his wife running for presidency).

- Repeat with me the Latin American mantra: Nothing Fucking Works®.

- Ask Haitians and Venezuelans how they’re treated.

I’d gladly post Batatinha’s pics if he was my dog, but my cousin would probably get annoyed, it’s a privacy matter.

But, basically: picture a huge dog. By “huge” I mean, he probably weights 40kg or so. Mostly black, with some tan; it doesn’t follow the same pattern as the Rottweiler or the German shepherd, it’s different. Short hair, floppy ears. Rather intimidating, I wouldn’t go anywhere close to that dog without my uncle or my cousin nearby.

I spend most of my day reading, as a translator. But it’s almost always stuff that I wouldn’t read, if not being paid to.

If counting only books that I read for fun, I guess it’s ~2 books/month? Typically fantasy light novels. I also read a fair bit of manga (~5 chapters/day).

Beyond those LNs I think that the last book I’ve read was in September; Um Copo de Cólera (lit. “a glass of rage”), from Raduan Nassar. Short but good first person story.

I’m almost 40. I’m… tired. I don’t read stuff to feel myself cultured; I read stuff when I need to (because of my job) or when I feel in the mood to do so.

My relatives do it all the time. On purpose. Cue to

- Átila - named after Attila the Hun.

- Batatinha - roughly “little potato”.

Guess who’s the toy poodle and who’s the shepweiler.

3·3 days ago

3·3 days agoFederation woes?

Your comment has a different take though, and adding value to the discussion, it isn’t just the same as I said. Both are complementary.

That’s one of my cats.

The other wants to be cuddled 25h/day.