Hey all I just came across an emergency situation irl that I felt useless in because of how slowly I was thinking. Basically it was someone getting an epileptic seizure and I had the info in my head for what to do but I did end up freezing a bit before I did anything. Really didn’t like it. The person is fine now but if I had reacted faster, we might have been able to prevent a couple problems.

I’ve been in other emergencies before where I had to call the shots but I guess I want to think faster and keep it consistent at a higher level, and I want to improve on it for future scenarios, but what can I do to do that?

Edit: Just wanted to say thanks for everyone’s replies, I’ll be looking into a routine to acclimate myself with these kinds of situations

Exposure and repetition through low stakes practice.

When you are out and about, think about what you would do if x happened to y at the moment you’re there. Standing in line behind an older person and suddenly they collapse? Be observant and notice if they seemed stressed, swaying, or uneven on their feet; be ready to slow their fall—place them into the recovery position and point to someone and say “YOU, call [emergency service number]”.

There are many aspects and many levels of preparedness. Decide up front to what extent you will be involved.

Look no further than the world’s militaries for this. They drill drill drill until soldiers react automatically without having to think about how they will react in a hostile situation. Its not enough to learn what to do once if you want a fast response.

Protein breakfast, stay hydrated, avoid sugar due to crashes. Also sounds like anxiety so exercise, treatment for that, etc

There are two aspects to being prepared and actionable:

- Action knowledge/confidence in knowledge

- Not being surprised into freezing/shock

You can lessen your surprise through:

- Experience

- Practice situations for automatism/intuitive reaction

- Consciously playing it in your head

Like playing physical actions in your head before executing them improves how you do them, playing situations through in your head can prepare you/your mind-space for them.

The majority of effort for emergency preparedness is repetition so you don’t have to think about it. Understanding is good too, but in a lot of cases you shouldn’t be taking action based on speed if you don’t know the right thing.

For example, it is generally better to just make sure someone having a seizure has room and isn’t going to fall off something. Things like sticking stuff in their mouth like in the movies is a terrible idea that makes the situation worse, so not acting is actually better than acting most of the time in the case of seizures.

As a counterexample choking requires immediate and correct actions. Some things will expel the object and others will get it stuck in a harder to expel location, so bboth time and foreknowledge is important.

All you can do is learn about the right things to do, such as taking a first aid class, and practicing them so you don’t need to think about what to do.

I think you basically just need experience/practice. Imagine lifeguarding: they don’t just explain it to you and then hope you remember what to do the first time you see someone you think might be drowning. They train you and have you ‘rescue’ people in a controlled environment, so that when the real thing happens, you’re performing something you’ve done many times.

To put it another way, you don’t want to think faster. You want to have already thought about it, and already prepared for what to do.

Depending on the extent of what you want to do, maybe a few friends and you can try to rehearse your response. Have them simulate (without telling you exactly when) some of the signs of a seizure, then try to identify it and give their phone a call as if you were calling emergency services.

If you want to go further you can look into various first aid certs. Most classes are like $20-60, and they’ll be able to prepare you far better than anything else.

For context: Not the same thing exactly but I had to get first aid certifications in the context of bringing small groups of people into semi-remote areas of nature. Type of thing where you probably have cell service but it may take hours for help to arrive. We did a lot of practice on each other.

As someone who used to be a lifeguard, it’s 99% boredom and 1% pure adrenaline. I only had to jump on once and it was for a toddler at swim class. They didn’t have floaties on and were sitting on the side of the pool. The instructor was in the water with another kid with no floats and the one on the side of the pool slipped in and sank. The instructor couldn’t just let go of the other child so I jumped in and pulled the kid out. There was no thinking just doing. I didn’t realize until afterward I’d cut up my foot relatively bad when I reacted but couldn’t even feel it getting the kid.

Training / Rehearsal.

That is the only proven method,

and that is exactly why some jurisdictions require, by regulations, a fire-drill for buildings with more than a certain number of people in them:

to prevent wrong-response, including freezing-up.

Take a 1st-aid refresher every 3y at-most, and it’ll make a big difference ( every 1/2y is optimal, but more costly ).

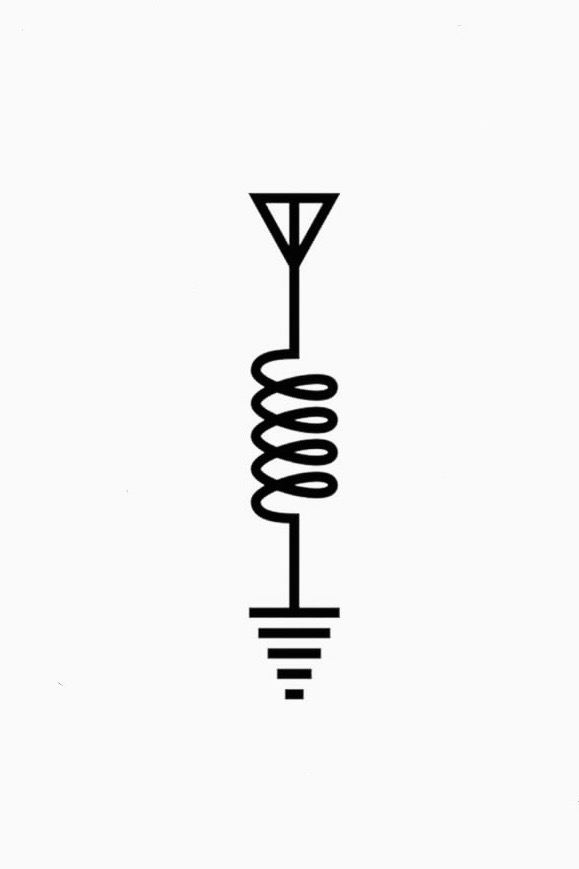

_ /\ _

Sign up for volunteer civil services that have to deal with emergencies.

It’s okay not to react quickly and clearly in an emergency, you have limited experience at it.

If you want to get better at emergencies, the thing that helps beyond training and practice is experience. Volunteer firefighter, care home, EMT work, any service or job where you have a higher chance to deal with emergencies.

You’ll get the training and you’ll get the experience.

Situational awareness. Read the room and try to anticipate problems in advance, rather than living on autopilot.

Reflective practice. You need to actually carry out all the actions needed for a scenario, then afterwards go back over how it went and plan for improvement.

That’s how we do it in hospitals, except the scenarios are real.

Intense situations like that are tricky because they don’t happen very often. Really the only way to get better at keeping your cool in tough situations is practice.

It is largely practice. For hospital based emergencies we practice common scenarios so that you’re not needing to think about the basics during an emergency. So for example learning how to use a crash trolley, how to do basic and advanced life support etc. Different areas will also have scenarios relevant to them - radiology may have have anaphylaxis drills to ensure contrast reactions are dealt with.

But practicing being in any emergency in general helps. You learn how to step back emotionally in any emergency and think. The lack of familiarity and panic is a natural feeling when you don’t know what to do but learning how to deal with potential expected scenarios makes you better at dealing with unexpected scenarios in general.

A good thing for most people to do even if not medical is go on a basic life support course. It’s a useful life skill but also opens the door to “how to think in an emergency”. Do it every year to keep fresh.

Other thing to learn is situational awareness - that is keeping your brain switched on when you enter new or familiar areas. It’s a skill that can be learned and translates well into emergencies. For example, when you go to a new place actively think “where are the fire exits?”, “what are my escape routes?”, “who is here now?”, “are there any threats here?”. These are things that can seem odd when you first do them but if you do them everywhere you go it becomes second nature and you start doing it subconsciously.

You’ll find people who work in hospitals, ambulances, fire brigade, police, the army and more are either directly or indirectly trained to do this. Admittedly not everyone in those areas actually learn it in the same way and some may learn “by accident” or as a side effect of other skills learnt.

Like for example, a nurse may not be taught formally “learn the escape routes everywhere you go” but they will be taught “listen to that alarm, if you hear it you need to do this” and “this is the fire evacuation plan for this floor” or “keep an eye on bed 3, their oxygen sats have been low today” and it can sort of seep in to how you perceive everything. If you’re in a noisy, busy and safety focused environment all the time you learn how to adapt and perceive what is going on around you even if you’re not consciously aware of that skill or what you’re doing.

I think most people can learn these skills. Like anything it takes practice.

Smoke less weed.

Don’t feel bad, this is the reaction most people will have in a medical emergency.

As others have said, you need actionable knowledge and practice. Experienced emergency providers don’t have to think much to stabilise a patient, its all ingrained and practiced, almost like a reflex. A good team can deal with most emergencies efficiently without communication (not that they should).

Of all the interventions you could do during an emergency, heres the most important ones, find a way to practice them:

-

Assess safety (this includes not touching blood with bare hands) and Call for help. Even experienced providers forget this, because noone practices this. Your first instinct should be this in any emergency. When you practice, you should always practice this step too even if you just audibly day “I check for safety and look for help”, ideally you practice yelling for help.

-

Quality chest compressions, minimise downtime. Mouth to mouth is great, but not as important and not mandatory for bystanders, although it becomes more important in drowning and in younger people.

-

Asphyxiation - back slaps (strong, not pats) and abdominal thrusts.

-

Applying pressure to a bleeding wound. With gloves or the sole of your shoe on dressing.

-

Stable side laying position - in any unconscious person without the need for any of the above. This is the one and only thing you do during epileptic seizures too. Do not shove things into unconscious peoples mouths…

-

Ideally you know how to free up an airway via chin lift.

If you can practice these, you can actually save a life in an emergency.

-

Create ipotetical emercency scenarios in your mind and elaborate possible solutions and way to handle that. Then look about your solution and think about what could go well and what could go wrong.

It’s not about cognitive abilities, it’s about having availability for possible strategies in your mind.